21 October 2022

Finding and Making

I spent the last two weeks in Budapest visiting coworkers. Alongside goulash, bathhouses, and palinka, I enjoyed learning a Hungarian folk saying: A sült galamb nem repül a szájába, or “A roasted pigeon will not fly into one’s mouth.”

A century ago, Hungarians in the countryside ate roasted quail (or pigeons, I guess). The folk wisdom claims that if we wanted to eat a roasted pigeon, we couldn’t wait around for one to find us. We had to hunt the bird, kill it, clean it, and roast it.

The same is true of ideas. We can’t loiter around, our creative mouths slack-jawed, waiting for a business concept or story plot to fly into them. A screenwriter won’t find the spark for a script alone in her apartment. She’ll discover inspiration as she speaks with the guy who runs the corner store, walks through a park she’s never visited, or reads a new book. The world is crawling with ideas, but we must go out and pluck them.

However, the perfect idea might not exist. If we spend all our time searching for the ideal image in our heads, we could end up empty-handed. Because ideas aren’t just found; they’re made.

My favorite Latin phrase is verum ipsum factum: We only know what we make. If we’re learning something new, the act of synthesizing will solidify our understanding better than anything else. We can read about computer science all day, but we’ll never truly understand until we put our fingers on a keyboard to code a program.

Likewise, we can’t understand an idea until we try to make something from it. We might discover a great story concept, but until we try writing the story, we won’t know if the idea is usable. That’s because the act of making involves the details—we must reconcile the intricacies and nuances to make something work. Without getting our hands dirty with the idea, it will remain theoretical and out of touch.

As we attempt to make an idea—flesh it out, frame it, get to know its textures—we might have insufficient raw material to bring it to life.

So, we do more finding.

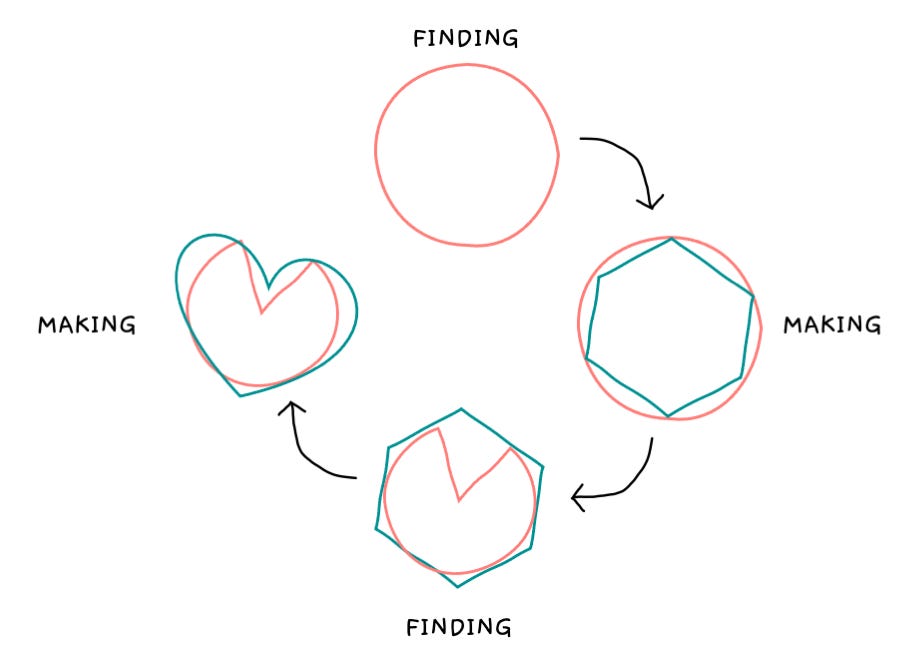

We seek new perspectives to add dimensions or combine new concepts to see what sticks. Generating new ideas is a loop of finding and making.

This loop can be big or small. In our romantic lives, we seek our idea of a great partner through dating. No matter how perfect a found person may be, we must work to make the partnership effective. We find new dimensions about the person and make our relationship with them different—more fitting—as we process more information.

On a smaller scale, we might find a new quote intriguing. Once we journal about the idea and relate it to our experiences, it will resonate deeper.

If you’re struggling to generate ideas, ask yourself: Do I have a finding problem or a making problem?