17 September 2022

Exploring the Great Lake of Knowledge

Should we generalize or specialize?

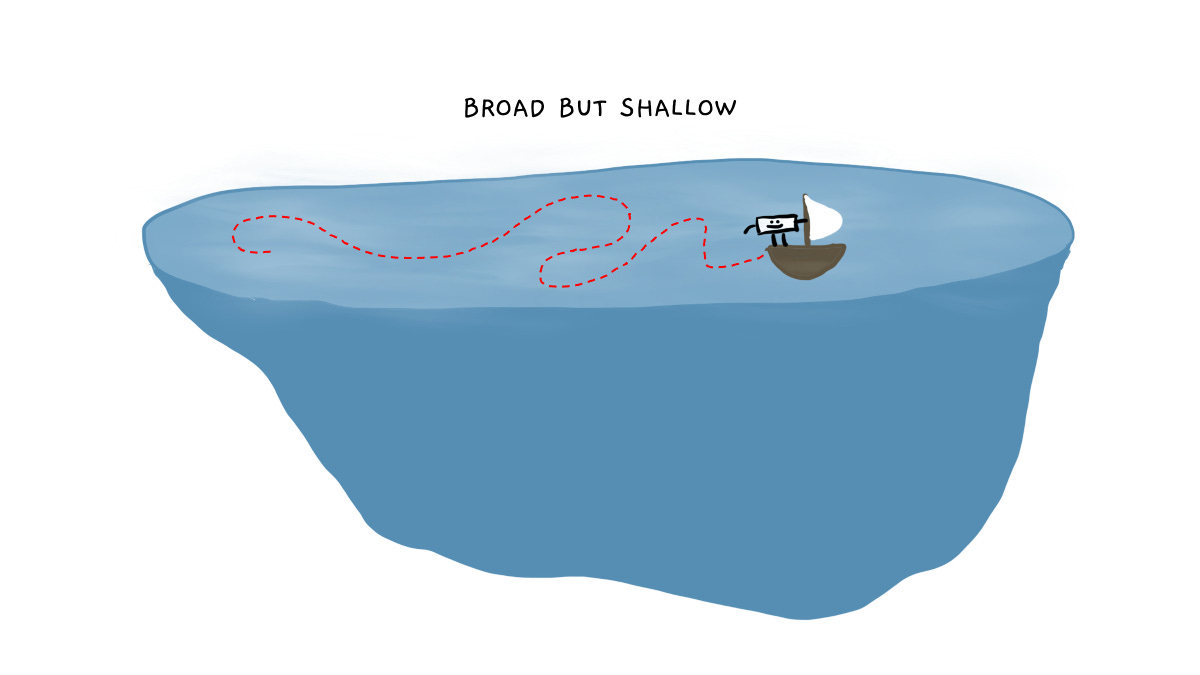

What if there was a sixth Great Lake? Beyond Michigan, Huron, Erie, Ontario, and Superior imagine you visited the Great Lake of Knowledge. You see waves going on for miles from your place on the beach, and you wonder what dwells along the shoreline or lurks beneath the surface. How would you explore this lake?

The Generalist

You might hop in a boat to survey the shoreline if you have a pioneering spirit.

Early explorers traversed land and sea to discover new territory, just as early pioneers in the arts & sciences developed new fields of study. Entrepreneurs carve new businesses from scratch, going from zero to one to establish baselines for future growth—building a product, finding customers, and establishing operations.

Generalists skim a large surface area. They have breadth.

Some generalists consider themselves “Renaissance men,” a nod to 15th-century Italians like Leonardo da Vinci, who had a breadth of skills in painting, science, music, invention, and writing. However, 1400s Italy was a very different time than today. During this period, educated men had few contemporaries with equivalent education and resources. Due to this shortage of educated people, Renaissance men had a lot of unclaimed intellectual territory to explore, so it made sense to dabble and still make meaningful progress in several newly defined fields.Things are different today—most people are literate, and many fields & industries have formed a deep corpus of knowledge. So, a true “jack of all trades” can never master anything since the bar for mastery is much higher than in Renaissance Italy.

That’s not to say a breadth of knowledge is useless—it’s just “high level,” and high-level knowledge is a commodity in the Information Age. Plus, the pursuit of breadth alone misses out on the richness of life.

A rolling stone gathers no moss.The Specialist

But maybe skimming the lake’s surface doesn’t interest you, so you picked up the diving gear and leaped into the depths.

After pioneers settled “new” lands or established new fields, more people became educated and capable of contributing to the new territory—physical or intellectual. As the industrial revolution redefined business, an intelligent strategy became niche ownership. Companies fragmented into smaller and smaller units of focus—specializing in specific processes, parts, or areas of knowledge. For instance, the auto industry spawned specialized companies for tires, lug nuts, paint, and seatbelts.

Specialists dive into a narrow domain. They have depth.

Some say that specialists “miss the bigger picture” because they only know the murky depths of a subject. I think that’s an unfair critique driven by language. The word “deep” in English has a connotation of downward movement, but I believe the Latin term altus provides a more nuanced definition. Altus meant “high” and “deep”—anything along a vertical dimension. In the same way, a specialist is not inherently “lost in the weeds”—they likely have a complete understanding of their domain.Consider a software engineer focused on computer vision research for artificial intelligence. They’re a specialist, as they know the technical intricacies and the high-level use cases for the subject. Being a specialist like this can be highly profitable and enriching.

However, specialization can leave one fragile. Like a koala who can only dwell in forests with eucalyptus leaves, specialists can be vulnerable if their niches go away.

Also, the pursuit of depth alone can be limiting. In our “Age of Specialization,” kids may restrict themselves to one sport to compete—missing out on various play activities.

There’s more to life than one little corner.T-Shaped

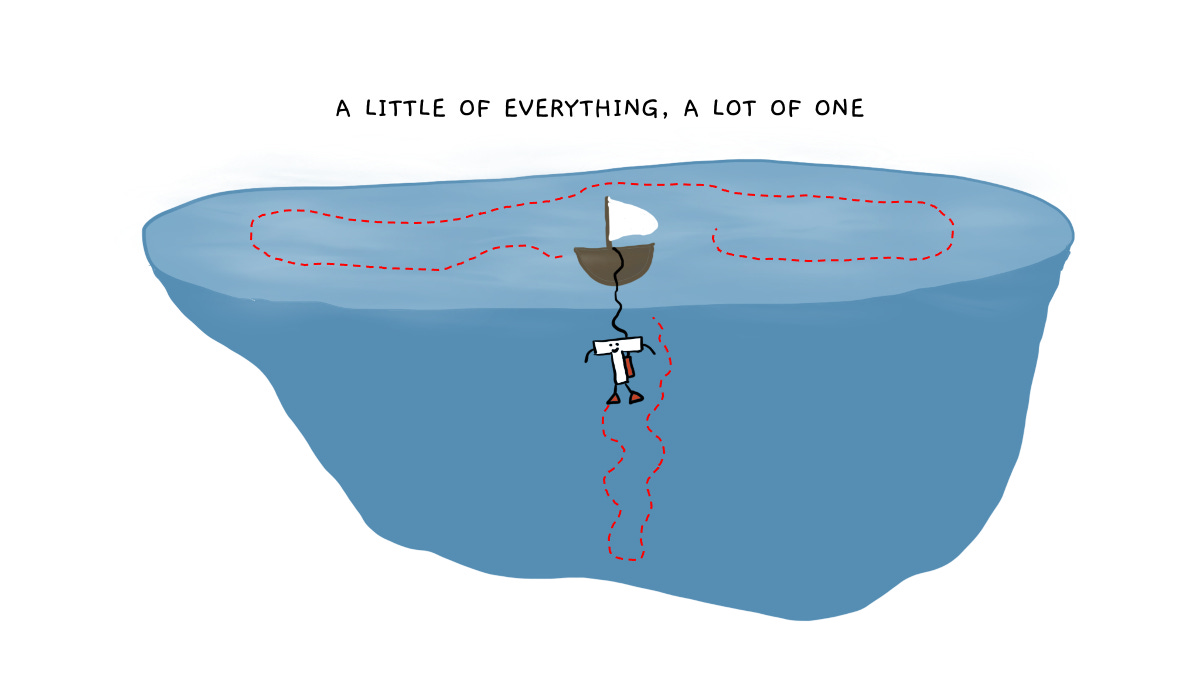

What if you could use both the boat and diving gear?

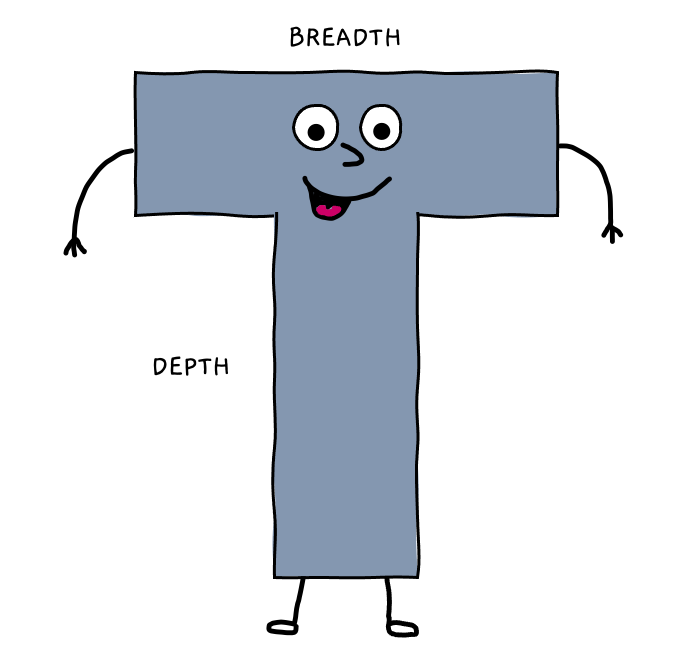

You don’t have to be a generalist or a specialist—you could become “T-shaped.”

T-shaped people have a shallow breadth of knowledge and a narrow depth of expertise in one area. Breadth is the “bar” of the T, and depth is the “stem.” A UX designer could be excellent at graphic art (the stem) and know a little about sales, front-end development, philosophy, psychology, and analytics (the bar). A T-shaped designer could use their breadth of knowledge to influence their primary craft (i.e., apply psychology to a color palette) and better relate to subject-matter experts (i.e., understand how a design could complicate front-end development).In defining the boundaries of their knowledge, T-shaped people gain self-awareness. They know when it’s appropriate to enlist help, which makes them more successful. Generalists might lean on a bunch of specialists to get anything done, which leaves them without the strong perspective needed to drive real progress. Specialists might become arrogant, assume they know everything, and not ask for help—sabotaging progress.

Expanding Breadth & Depth

By boat, you peruse the lake’s surface but never see the richness below. By diving, you explore the depths near shore but never discover wonders across the lake. Using both the boat and diving gear lets you fully experience the lake.

To expand your breadth and depth:- Improve Concentration to gain mastery in a single domain.

- Increase Resiliency to persist through the challenges of seeking depth.

- Read Broadly to stay curious and expand your awareness.

- Actively Dabble with hobbies and interests to learn new skills.

Over time, your bar will deepen, and your stem will widen.

The lake’s too large and exciting to only skim the surface or dive in one cove.