02 December 2022

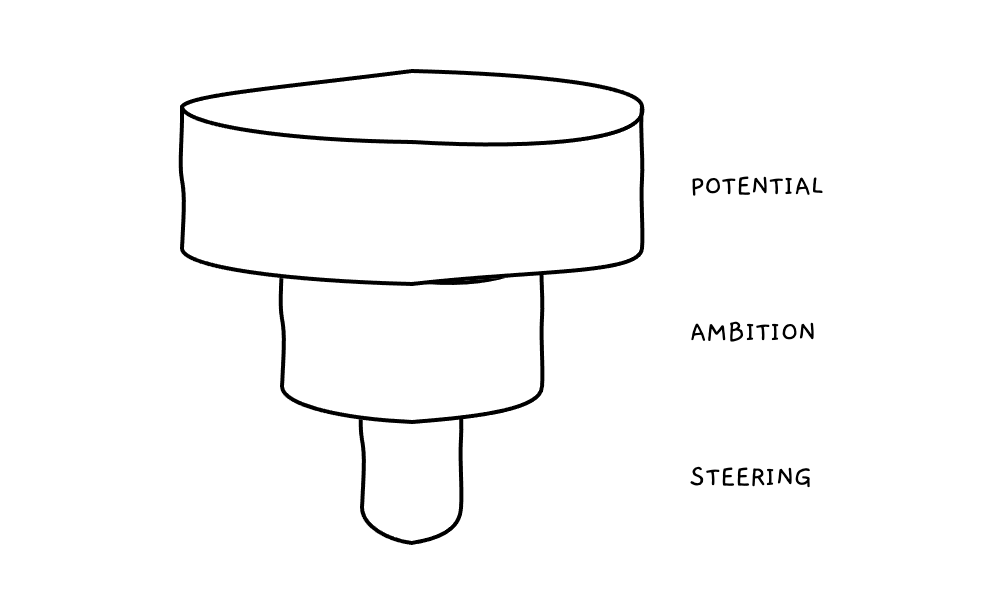

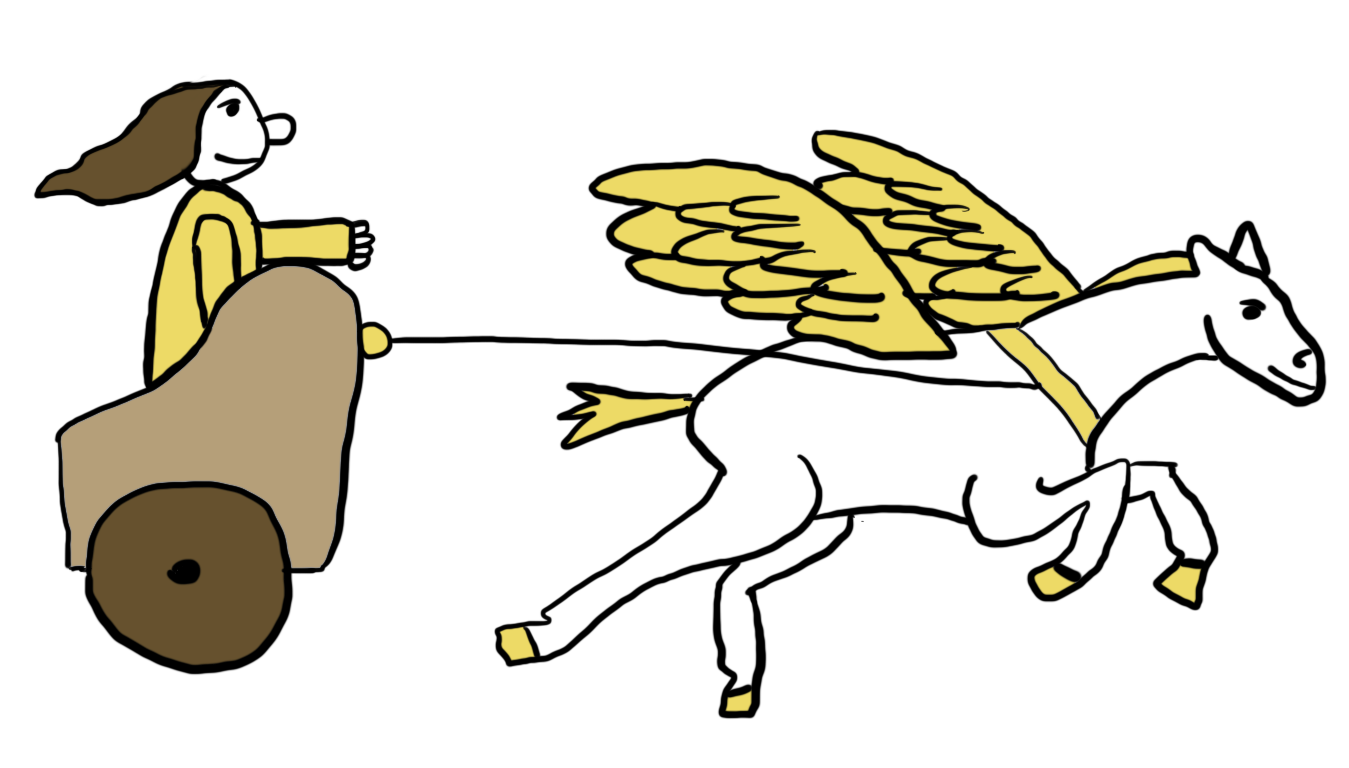

Steering Pegasus

Everyone has the potential to do great things, and I’d venture half of us have the ambition to realize that potential. But few can manage the pull of ambition.

Handling Vice

As humans, we crave comfort and pleasure—valid pursuits we ought to enjoy. But we can struggle to balance the impulses that create them. Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics labels these temptations as vices—things that do not lead us toward our goals. We know the classic vices of smoking, alcohol, gambling, sugar, or shiny objects. I don’t believe these are inherently “bad” pursuits, and some could argue that everyone has a vice. I’ve rejected this idea for years—an act of puritanical self-righteousness—but have come to accept it. Even without a classic vice, plenty of activities exist to relax or relieve stress. While I don’t smoke or gamble, I enjoy beer, coffee, incessant gum-chewing, TV, and the occasional doom scroll on Twitter.

Handling Virtue

We can define virtue as something that moves us toward an objective or ideal. For instance, “hard work” can help us achieve more in our careers. A virtue of health can enable us to live longer, achieve athletic endeavors, or play basketball with our grandkids.

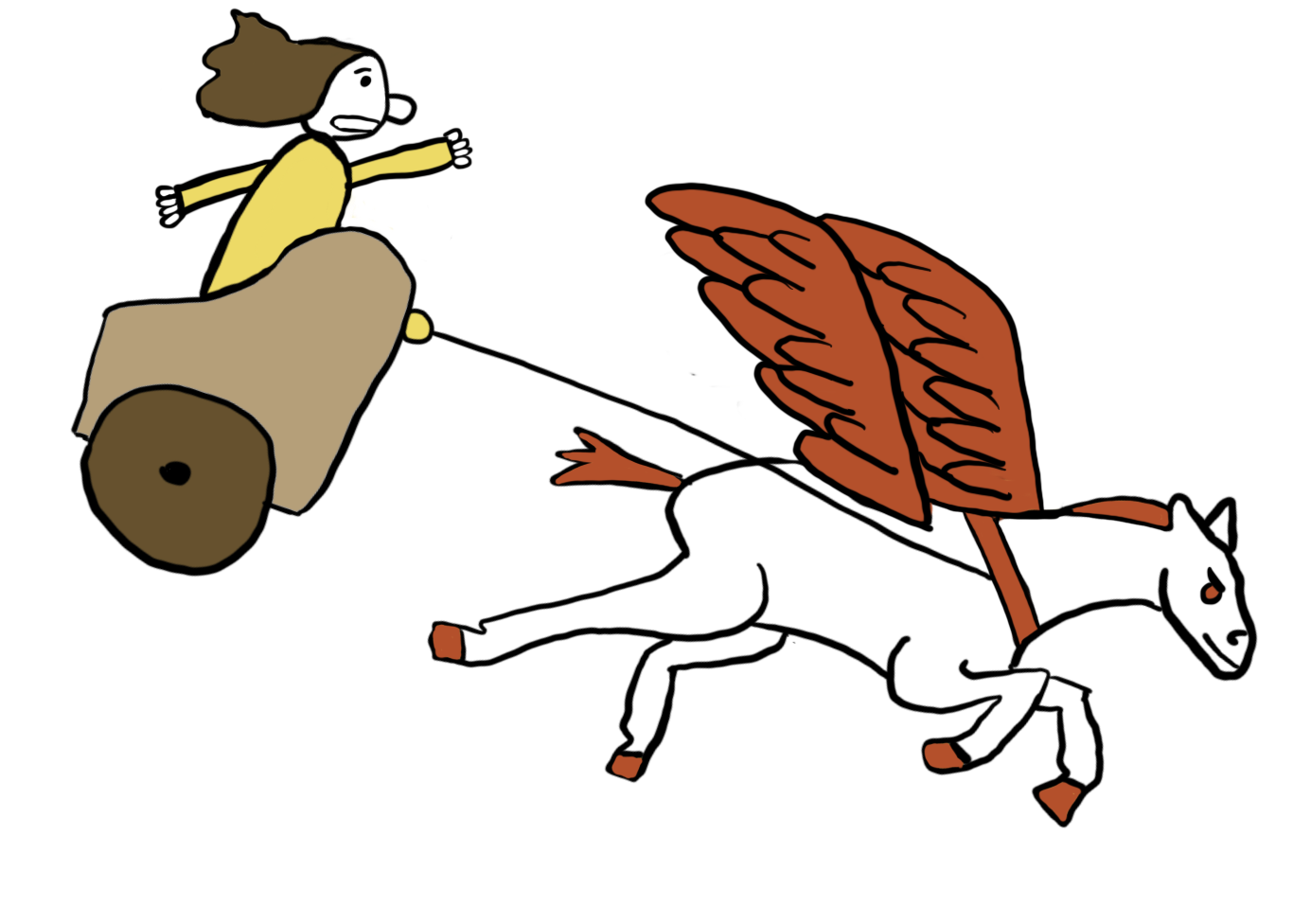

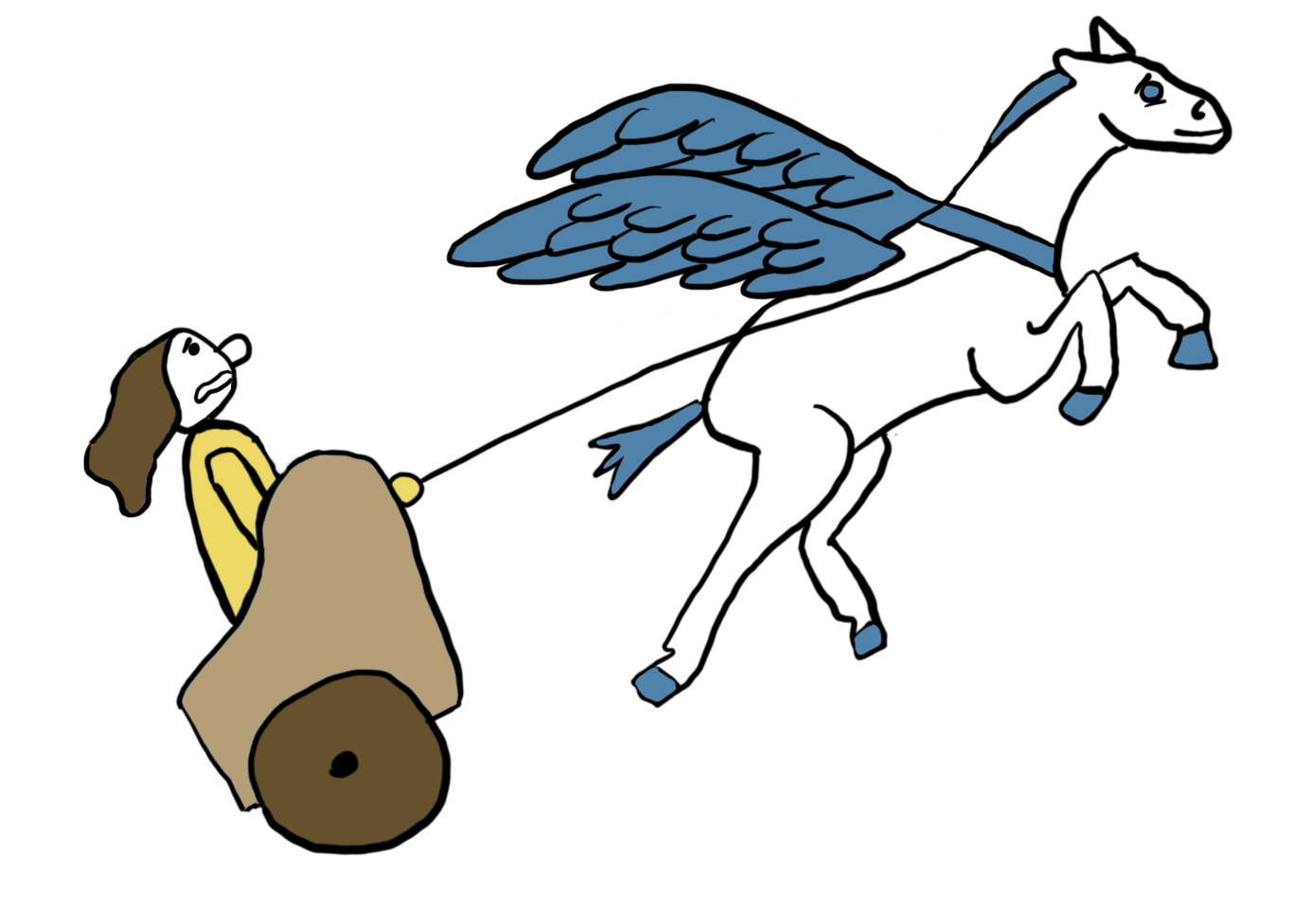

At face value, virtues may seem objectively good, but we can have too much of a good thing. If virtues go unchecked, they can lead us astray. When the overambitious Pegasus ascends too high, we burn up in the atmosphere and experience burnout.

Balance through Volatility

Without virtue, there’s no wind to lift the wings of our ambition. Without vice, we’ll burn ourselves out or ascend to a level of self-righteousness that makes us detestable to loved ones. Striking balance between virtue and vice requires us to acknowledge the good and evil—or, more accurately, the higher-minded ideals and animal desires—within us. We must believe that living with intentionality around our values is desirable while simultaneously accepting vices as vital to the human experience.

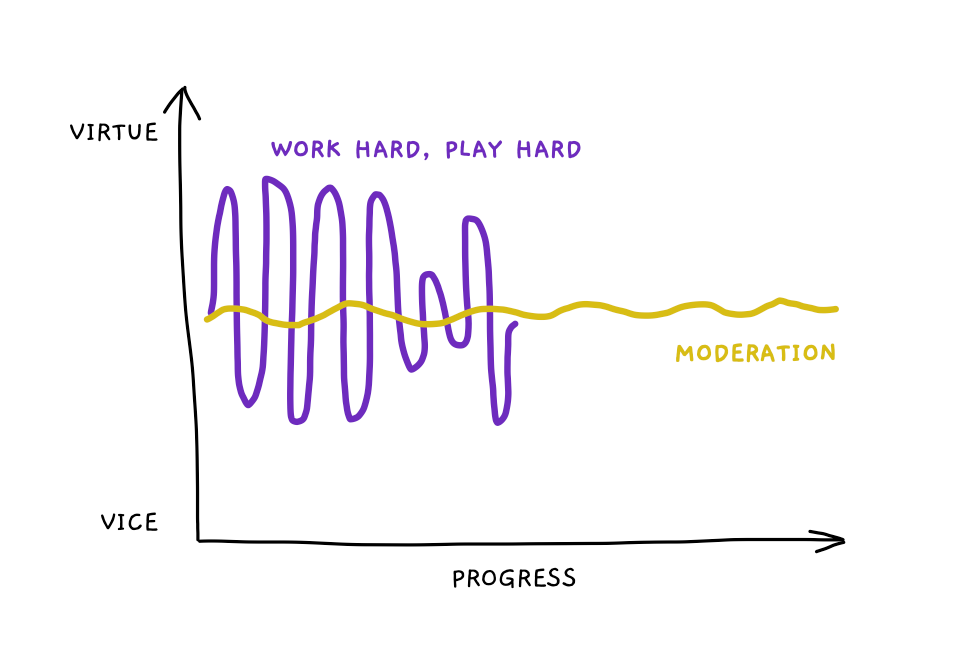

To strike this balance, some adopt the “work hard, play hard” mentality. In other words: An excess of virtue followed by an excess of vice. People may log sixteen-hour workdays and binge drink on weekends to unwind. While some circles may praise this hardcore industriousness, it’s ironically less productive in the long term.

A Middle Path

Most worthwhile endeavors require sustained effort, so it’s beneficial to bias sustainability over intensity. Sometimes we climb higher and drift lower to relax, but the overall trajectory should average a steady pace.

Consider fear. If viewed as a vice, we might value bravery as a virtue. But if we become reckless, we may throw all caution to the wind—turning our virtue into a vice of excess. Conversely, we could value conscientiousness as a virtue. Yet, we could become too cautious—avoid confronting people for fear of retaliation or social discomfort—and turn that value into a vice of deficiency: cowardice. The middle ground—courage—is challenging to tread, for we must acknowledge and experience fear but act despite it.

Once we decide on our virtues, we can manage our vices. One approach is to dilute our existing vices. For instance, if we want to limit alcohol intake, we could scratch the itch for a relaxing drink with a mocktail instead of a cocktail. Instead of zoning out and binge-watching TV, we could zone out on a long walk to decompress after work.

We need both vices and virtues to make progress on our goals. Rather than avoid vices entirely, we can pick ones that don’t unravel us. We cannot escape them, but we can learn to enjoy the journey of steering Pegasus.