08 June 2023

The Portmanteau Strategy

Urban planning nerds love to hate a stroad. “Too ugly!” they say, “Too dangerous!” Most towns built in the last century revolved around a car-centric lifestyle, which began to blur our concepts of urban infrastructure. A street is designed with pedestrians in mind—storefronts line its edges, traffic lights are frequent, and people mosey along its sidewalks. Conversely, a road is designed for fast travel, so traffic lights are infrequent, and no sidewalks border it. A stroad blends these concepts: often several lanes wide, interspersed with traffic lights and lined by unused sidewalks, drive-thrus, and car dealerships.

A stroad is a portmanteau, a fancy word that forces two words into one word. In much the same way, most portmanteaus force-fit two concepts into one:

- Spoon + fork = spork

- Breakfast + lunch = brunch

- Ankle + bracelet = anklet

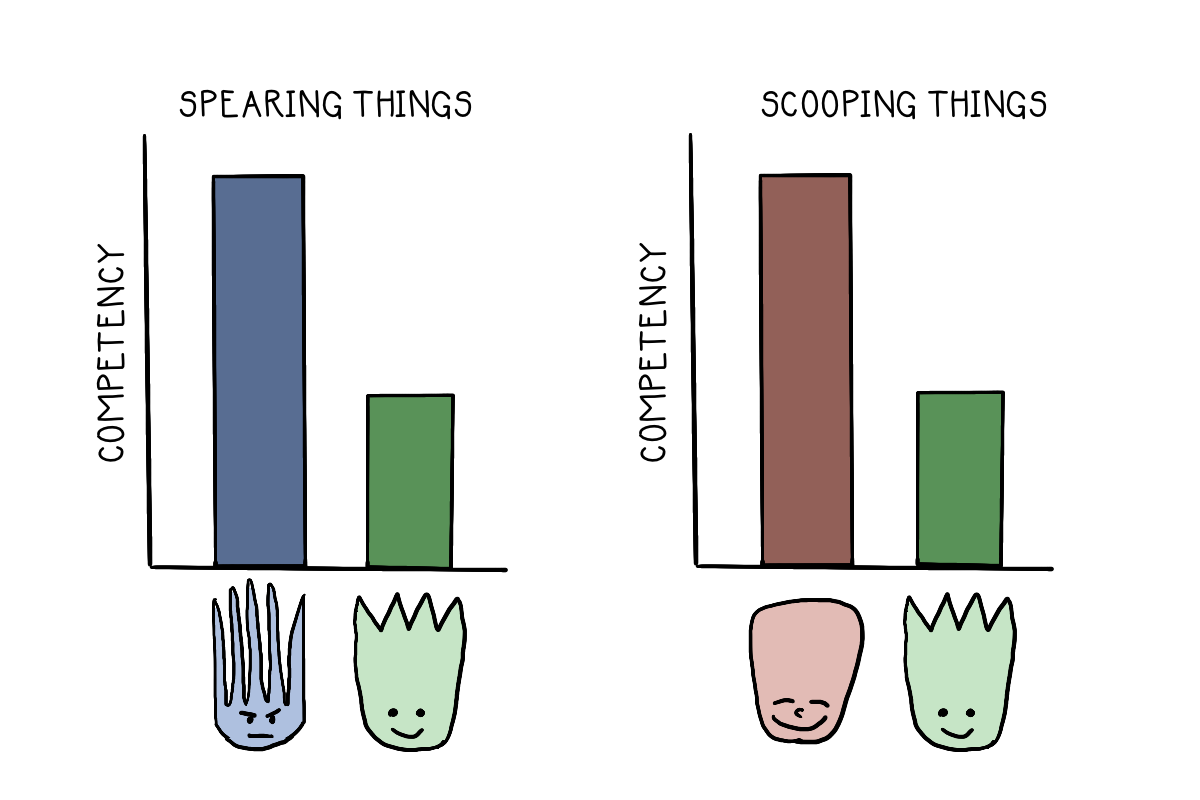

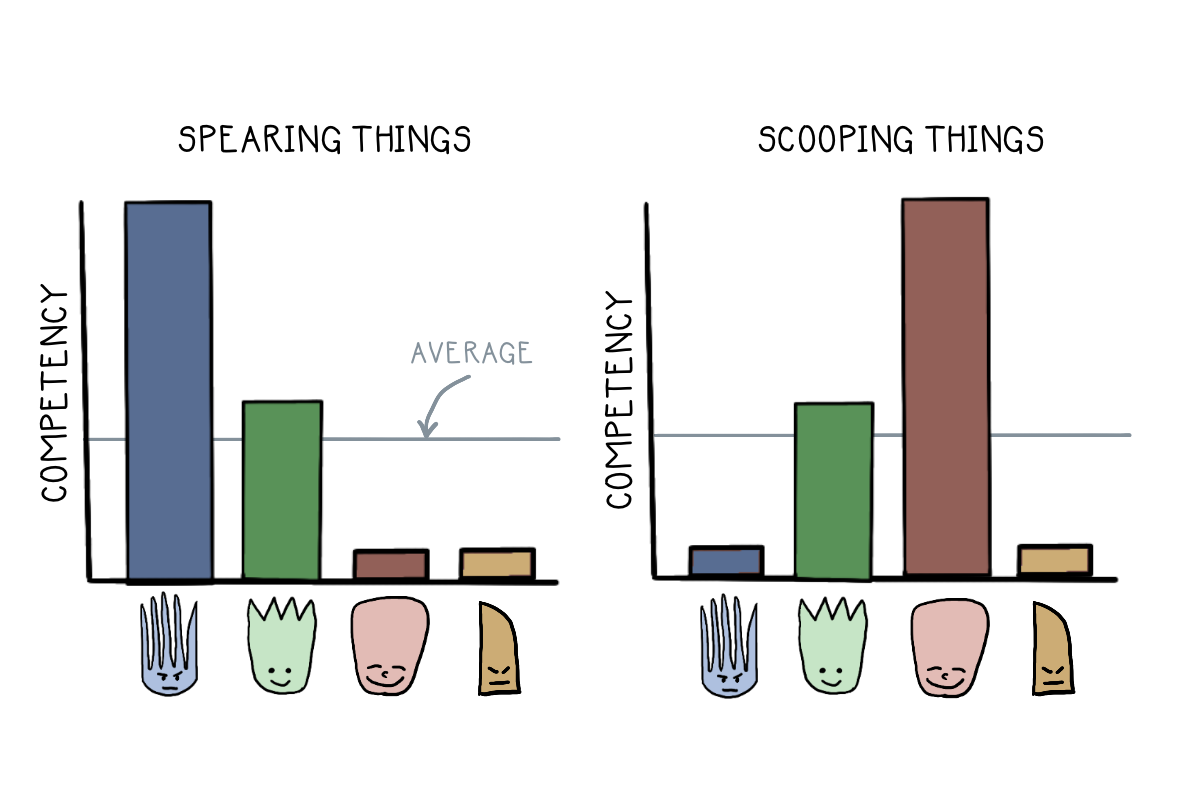

Despite the additive operation, the result is more like subtraction: 3 + 2 = 1. A spork is worse than a fork at spearing things and worse than a spoon at scooping things. With this double mediocrity, it’s a wonder how portmanteaus exist.

Portmanteaus not only work for objects and concepts, but they apply to careers. Scott Adams, creator of the Dilbert comics, glibly describes his talent-stacking approach to career success:

“I can draw better than most people, but I’m hardly an artist. And I’m not funnier than the average standup comedian, but I’m funnier than most people. The magic is that few people can draw well and write jokes, so the combination of the two makes what I do rare.”

Scott Adams was a decent cartoonist, joke writer, and businessman who wasn’t exceptional at any of the three. But when he stacked these talents, he created a niche where he could thrive: Office humor cartoon panels.

Conventional advice tells us to focus on one thing and do it better than anyone else. A common pushback to that argument is “specialization is for insects,” an excuse for pursuing a shotgun strategy to be subpar at a dozen things. But let’s pull the rope sideways. Rather than be the best at one thing or average at several things, be above-average at two or three things.

Talent-stacking is a portmanteau strategy that can give us a blue ocean of opportunity because we’re no longer competing to reach one of a few coveted spots. It’s an exciting idea to unlock creative potential.

The portmanteau strategy is easier said than done. The discerning reader may return to the stroad—the ugly infrastructure that ruins pedestrianism—and see talent-staking as a recipe for mediocrity. Instead of striving in a discipline, one can hack together disparate skills, call it something French, and peddle it off as “uniquely positioned.” This perspective is valid: Portmanteaus can be inelegant and don’t conform to conventional definitions of excellence. But this pessimistic take doesn’t accomplish much.

Thomas Friedman, a three-time Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist for The New York Times, once wrote, “Pessimists are usually right, and optimists are usually wrong, but all the great changes have been accomplished by optimists.”

If the natural selection of a free market can let a portmanteau survive, perhaps a portmanteau strategy could help us thrive.