21 July 2022

Recursive Pareto

A rook, a bishop, and a pawn discovered a scroll. The pawn unrolled the parchment and read, “Buried treasure lies beneath the chessboard. Whoever amasses the greatest riches will rule the board.”

The rook leaped to the chessboard and ran across the first rank. He dug each square and found small coins beneath them. He greedily shoveled the change into his tower, chuckling as the nickels and dimes jingled inside him like a porcelain piggy bank.

The bishop and the pawn exchanged a glance. Sixty-four squares were a large surface area, and neither the bishop nor the pawn could move as efficiently as the rook. But they didn’t need to because they knew:

The Pareto Principle

Also known as the “80-20 Rule,” the Pareto Principle states that 80% of the benefit comes from 20% of the effort. The idea originated from economist Vilfredo Pareto, who observed that 20% of Italy’s population owned 80% of the land. A similar pattern exists for global wealth distribution, software bug management, baseball players, product lines, occupational hazards, and more. The Pareto Principle is effective for many situations, even bizarre, anthropomorphic chess piece treasure hunts.

Rather than scour the whole board for small coins, the bishop and the pawn could search 20-25% of the board for bigger treasures.

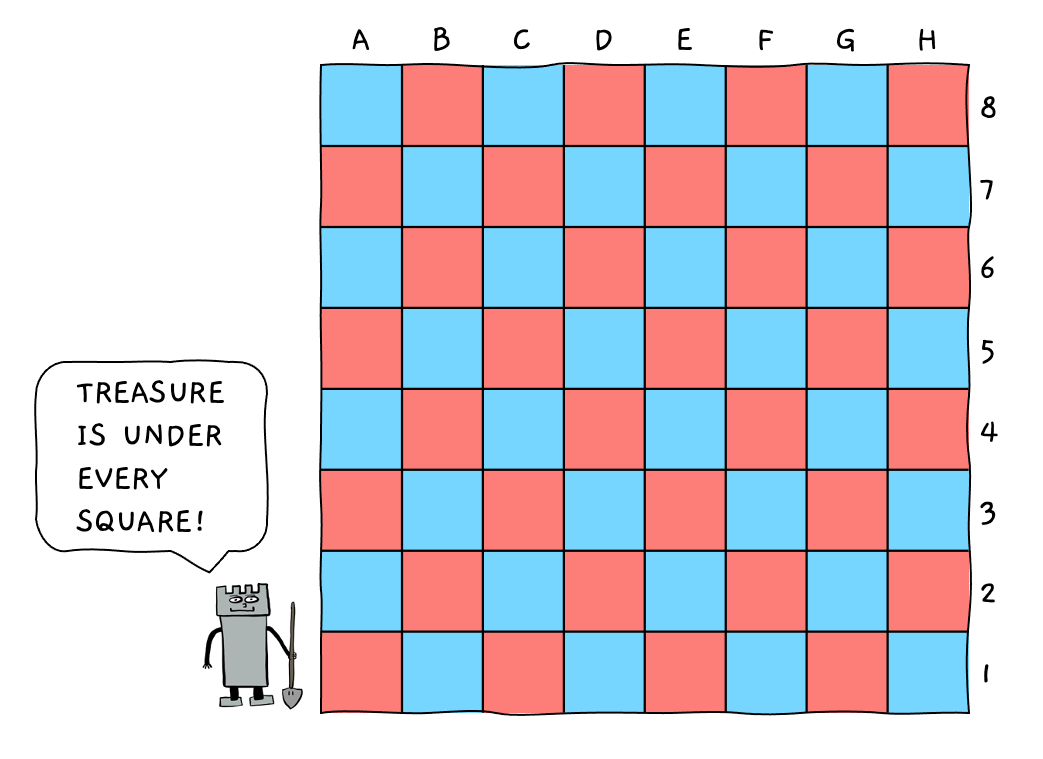

While the rook ran around, busily collecting small prizes, the bishop and the pawn kept reading: “—but more treasure lies beneath blue squares on the top half of the board—”

Excited by the news, the color-bound bishop darted diagonally across the top half of the board. He giggled as he unearthed gold bars from blue squares.

But she didn’t need to check the first 20% of squares. She knew:

Recursion

You’ve likely seen a photo of a photo. If not, imagine a picture of a room with a picture of the room hanging on the wall. In that picture, there’s a picture of the picture of the room. And so on.

Recursion is when one step in a procedure invokes the procedure itself. In computer science, a recursive function can call itself until it reaches a logical conclusion. Making a sourdough starter involves feeding some starter to the starter.

Recursion is like the mythical Ouroboros, a serpent eating its tail.

The pawn approached the board and looked at the blue squares in the 8th rank. These four squares contained 80% of 80% of the board’s total value: 64%. If the pawn salvaged the treasure beneath these squares, she’d have 64% of the riches—enough to rule the board!

Recursive Pareto

By applying the 80-20 rule on itself, you can narrow in on the highest value of the highest value. If you have 100 tasks on your to-do list, identify the top 20 that could deliver the most value. Once you have the top 20, select the top four from that list. Then, rerun Recursive Pareto to pick the single most valuable task.

The pawn only had time for one move, so she could randomly pick a square or keep reading. She glanced at the scroll: “—under square G8.”

80% of 80% of 80% was 51%. With one move, the pawn became the majority shareholder of the board. She donned the crown, claiming her rightful place as queen.