26 May 2023

Bike Commuting

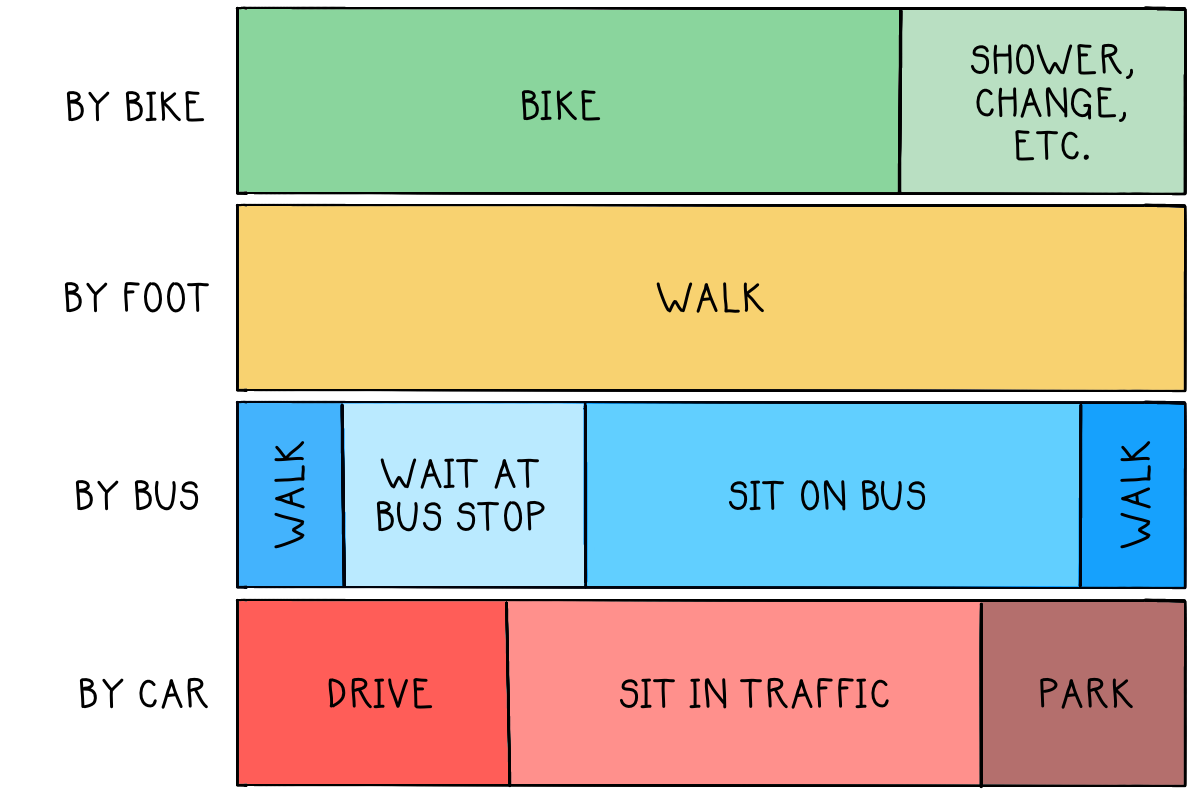

When my office reopened in 2022, I had to relearn commuting. I tried driving, but I couldn’t stomach the daily parking cost. I tried public transit, but the bus was often delayed and dirty. I even tried walking, but that took over an hour each way.

So, I chose to bike.

Funnily enough, each commute method took roughly the same time desk-to-desk.

Then I needed a lock for the bike and a lock for the gear I’d store in the locker room. To access the locker room, I had to email HR for a form, complete it, and deliver it to building management.

After a few commutes, my tire went flat because broken glass punctured the innertube. So, I got a patch kit and an air pump. To take the tire off, I needed tire levers.

When the temperature dropped, and I started wearing warmer clothes, I got ankle straps to keep my pant legs from getting caught in the chain.

After a while, the chain got dirty, so I needed lubricant. But I put on too much, which exacerbated the dirt problem, so I bought a chain brush and degreaser.

Then it got dark in the morning and evenings, so I needed front and rear bike lights.

Eventually, I got soaked by rain and puddles, so I installed fenders. That required another round of special hardware and a visit to the bike mechanic.

Several yak-shaving journeys later, I now happily and reliably bike commute to work, desk-to-desk in about fifty minutes.

Things are more complicated than they appear.

So yeah, bike commuting was more of a hassle than I initially anticipated. In theory, it sounded simple, but many little things had to happen to make the idea a reality. Beyond all the gear, I had to stay disciplined about the schedule, mentally prepare for poor weather, and react to unexpected hurdles (popped tires, getting hit by cars, forgetting things).

Joining a “small project” at work comes with two more weekly meetings, several more email chains, another Slack group, new docs to read, new processes to follow, and new stakeholders to appease. Gaining a friend comes with regular correspondence, fulfilling favors, and scheduling activities. Launching a product feature can require new technology, creating GTM collateral, defining communication plans, and setting up monitoring.

Things are more expensive than they appear.

At Walden Pond, Henry David Thoreau contemplated the economics of modern work. Since 60% of Americans are employees, a paycheck funds most U.S. livelihoods. Thoreau stated that we exchange our life energy for capital to spend on other things. So, when we purchase something, we’re sacrificing part of our life (i.e., 8 hours per weekday) for it. With this framing in mind, let’s calculate the cost of bike commuting:

Bike: $1600After-Market Components (Rack, Fenders, etc.): $200Riding Accessories (Bags, Helmet, etc.): $100Maintenance Accessories (Pump, Tools, etc.): $100

The raw financial cost of my bike was $2000, which I consider a one-time fee since most materials will last years. Applying a Thoreauvian lens, I’ll convert this back into life energy by considering my annual income. Let’s say that dollar-cost equals 2.5 days.

I also have light, ongoing time costs. Fixing a popped tire, greasing a chain, or cleaning the frame are ten-minute activities that occur a few times annually. Let’s say these cost two hours per year. Conservatively, my total cost of bike ownership was three days last year.

Knowing this hidden cost is powerful when making seemingly small decisions.

I visit the office twice weekly, and parking is $28/day. If I go in fifty weeks per year, I will spend $2800 on parking alone, assuming the garage doesn’t raise their rates (as they tend to do). Translating to life energy, $2800 is 3.5 days. While the cost difference between biking and driving seems trivial in year one, remember that driving is not a one-time cost. Even without considering fuel cost and inflation, I’m saving three days of life energy by biking this year! Plus, I get the boosted life energy that comes with regular outdoor exercise.

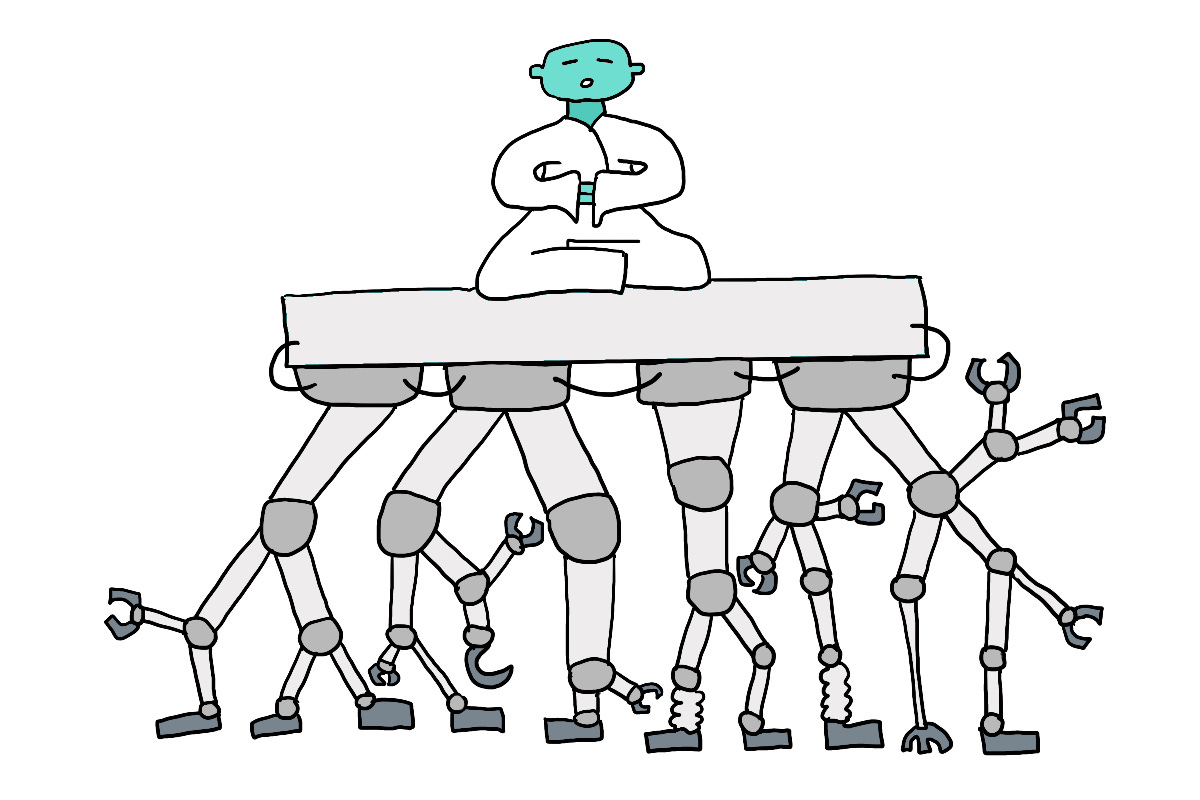

Vertical Ownership

Ownership can provide richness to our lives. But there’s a particular way of owning things to maximize life energy. In Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Robert Pirsig defines “quality” as simultaneously maintaining the gritty inner workings of a motorcycle and experiencing the joy and freedom of riding it.

One could theoretically outsource all maintenance and take their bike to a mechanic for regular tune-ups. I’m not against outsourcing and have paid a local mechanic for help with my fenders. However, outsourcing has a hidden cost: resiliency.

With bike commuting, I cherish the Zen-like days when everything just works—I roll the bike out the door, pedal under a cloudless sky, and arrive without issues. But something can easily disrupt that: A popped tire, rain, a displaced chain. Taking the time to fix the problem myself is satisfying, but the real benefit is more pragmatic. The knowledge and willingness to perform maintenance make me more resilient to issues, so I am unblocked from riding and can do so consistently. If I only lived at the Zen layer, I’d miss riding days by waiting for a mechanic.

The Merits of Maintenance

Maintenance has a bad connotation; it’s boring, requires no creativity, and should be automated. Not all these things are true, but even if parts of them are, they should not overshadow the importance.

Anything worth having requires maintenance. A car requires six-month tune-ups, family members need thoughtful attention, and consistent product updates drive loyal customers. Maintenance is an expression of love, and good maintenance separates flashes in the pan from lasting success.

This is not to say that things shouldn’t grow and change. As the old saying goes, “If you’re standing still, you’re falling behind.” It’s easy to misinterpret that quote as “Always innovate and pursue growth!” but that neglects the humbler and more essential component: maintenance.

We need to pedal the bicycle to go anywhere, but we can go farther and longer if we stop to inflate the tires.