08 September 2022

Creative Distillation

“I have only made this letter longer because I have not had the time to make it shorter.”

— Blaise Pascal, French mathematician, 1657

Imagine a world where ideas were concrete instead of abstract and thinking was a mechanical process. In this world, intellectuals have big funnels atop their heads to collect ideas. Here, ideas are not amorphous concepts but little marbles that spiral into brains filled with gears and levers. These “funnelheads” follow a four-part process to create new things for one another.

### CollectTo make anything, a funnelhead needs raw material. Houses need bricks, cars require metal, and abstract things—like music, literature, software, or scientific discovery—demand ideas.

Ideas, whether from media or conversations, fill the creative hopper. Then, the funnelhead’s brain cranks its gears to process the raw material, like a blender working through fruit and nuts.

Our source of creative insight is similar: We collect, whether consciously or unconsciously, knowledge and experience. Collection is only one-quarter of the creative process because, without subsequent action, it devolves to gluttony or empty calories.Diverge

To twist the knobs of this steampunk metaphor further: Once our minds start cranking, we churn out new ideas. We mix and experiment, generating many seemingly unrelated, “divergent” thoughts. Funnelheads experience a peculiar pleasure as they cough up wildly unique ideas. While social creatures, funnelheads like privacy during divergence because the mess of new material is personal.

Creativity can be mislabeled as the process of divergent thinking—conjuring images of artists drowning in paintings of their own creation. This generative aspect is romantic, but divergence is only the second quarter of the process. The purpose of making is to share something with others, so if our thoughts aren’t shareable, divergence is merely mental masturbation.Converge

Funnelheads, in the pursuit of creating something worth sharing, sift through their divergent results. They select a handful of concepts worth keeping and drop them back into the funnel to form new relationships and converge into a single, coherent idea.

Whether a research paper, website design, or newsletter—convergence synthesizes various ideas into one. Divergent threads come together, and we spawn something new. But convergence isn’t the final step of the process. Although a converged idea is more refined than a pile of divergent thoughts, it may have rough edges that leave it unshapely to others.Distill

The funnelhead drops the converged idea into its hopper once again.

And again.

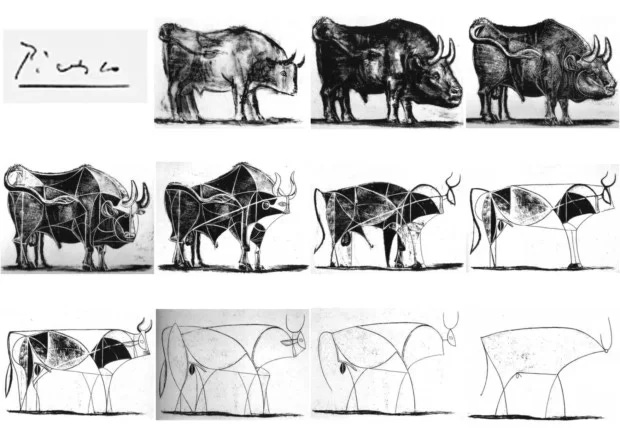

Funnelheads are ardent admirers of Pablo Picasso, the Spanish painter. In their schools, funnelheads are taught the merits of creative distillation through the story of Picasso’s Bull.If you see the painting, you might find it unimpressive—perhaps something you could draw. The image is disarmingly simple, especially when you see all the work that came before it.

When Picasso set out to create “The Bull,” he collected raw material from observing living bulls, formed divergent sketches, and then converged them into a single depiction. But the first drawing, to Picasso, was insufficient. He’d begun with a more realistic style—illustrating the bull’s muscles, fur, and horns in detail—but found the drawing inadequate to capture its core concept. So, he drew it repeatedly, stripping away unnecessary layers to reveal the essence.

Paradoxically, finding something’s simplest form can be a grandiose endeavor. To take a lumpy object and chip away to its core is truly an art—if not for the ability to kill one’s darlings, but for knowing when to stop. If distilled too much, you could produce an idea with no texture. For instance, I could have “sanded away” the funnelhead metaphor from this newsletter to deliver the same message. However, I felt I’d lose something in the process—perhaps the spirit of Turtle’s Pace (if “spirit” means bad doodles and unnecessarily strange metaphors). Distillation is an art; it requires feeling, judgment, and other squishy things that don’t fit into a framework. It’s the final quarter of the creative process and the piece we tend to overlook.When that happens, maybe a simple apology is best:

“If I had more time, I would have written a shorter newsletter.”