26 January 2023

Start with the Jar

If you’ve seen Rudolph: The Red-Nosed Reindeer, you’ll remember the Island of Misfit Toys. When sitting around a fire on Christmas Eve, the sad little misfit doll said, “I haven’t any dreams left to dream.” This line contains a profound but familiar sadness—giving up on a better future because of continual disappointment. The more we want and believe we can change, the more hopeful we are. When the world fails to meet those expectations, it betrays our hope, making us hesitant to hope again.

Optimism is dangerous, especially when it comes to planning our goals. If we underestimate the effort of an endeavor, we set ourselves up for failure. When we fail to meet our expectations, we can succumb to cynicism.

We must learn how much we can process to avoid the hope trap.

Domain, Duration, and Dimension

Imagine you have thousands of marbles to carry on a plane, and airport security released a new regulation that limits an individual to one jarful. If you don’t know the jar’s capacity, you won’t know how many marbles you can bring and could risk losing your precious orbs!

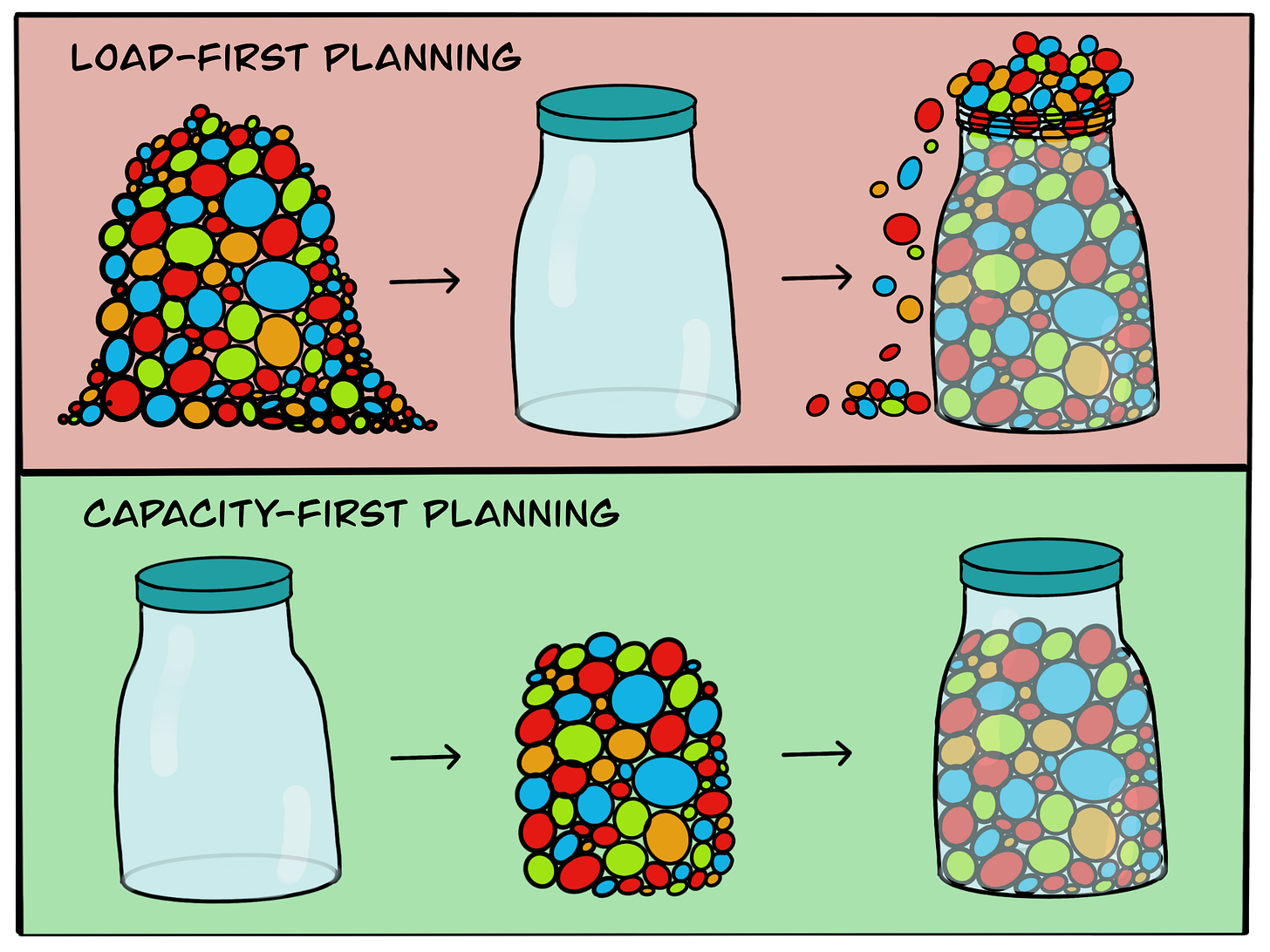

Traditional planning starts with the load—“I need to haul 500 marbles”—and seeks to find a suitable container. Load-first planning is sensible for physical goods, but when working with the squishy machines in our skulls, this approach creates problems. Capacity-first planning starts with the size of the jar before committing to marbles.

We might have the energy and motivation to ski every day, but we lack the time, so our skiing capacity is limited to once per week. Conversely, we might have the time and patience to read untranslated Russian novels, but we lack the energy to spend more than 30 minutes daily.

It’s helpful to pick one domain, duration, and dimension when measuring capacity.

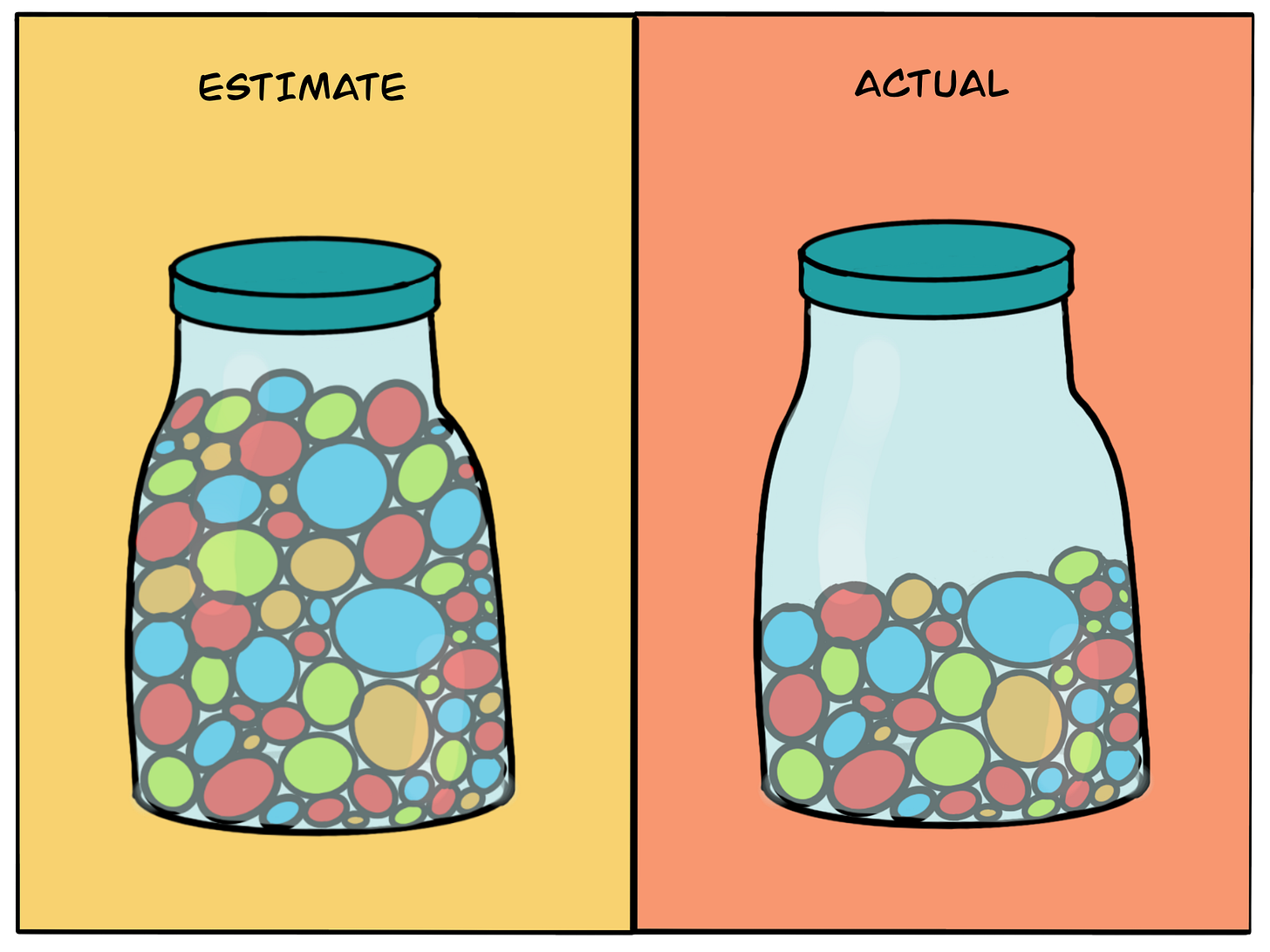

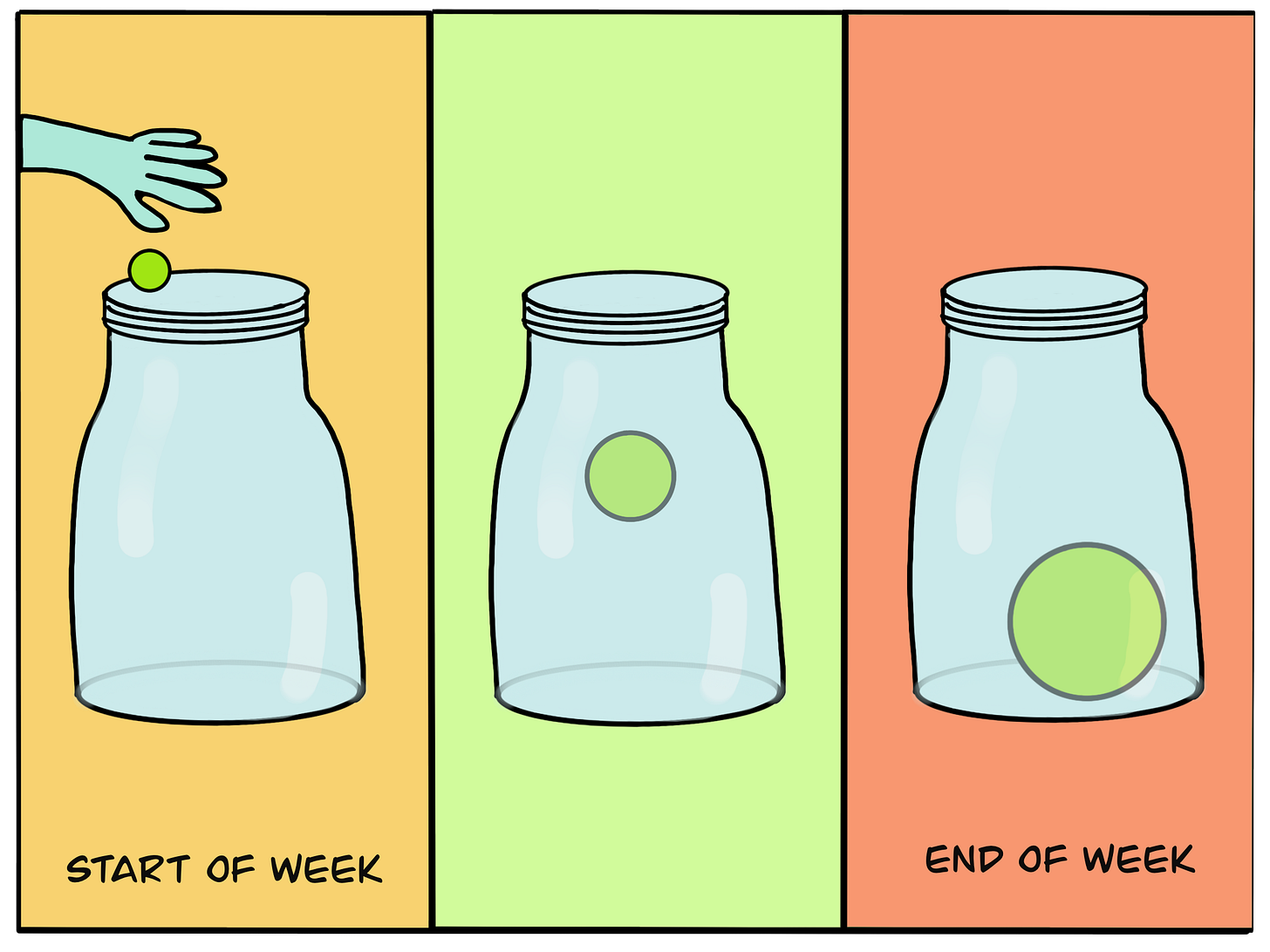

I recommend starting with weekly for the duration and time for the dimension. Estimate how many hours we’ll spend on a domain at the start of the week. At the week’s end, we’ll count the actual hours spent. We’ll do this for a few weeks and average the actual hours to get our capacity.

After measuring capacity, we’ll notice that things always take longer than expected.

“Hofstadter’s Law: It always take longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter’s Law”

– Douglas Hofstadter, cognitive scientist

When dropping marbles into a jar, it can feel like they undergo perpetual expansion—constantly growing to fill the space. Although Hofstadter’s Law claims we cannot avoid this, I’ve learned a trick to reduce its impact: take 70%.

After reviewing our available hours, we only schedule 70% of the available capacity. If we think we’ll have ten hours, we plan for seven.

Maximizing Usable Space

We have 24 hours a day, but viewing 24 hours as our jar’s fixed capacity is limiting. Capacity is more than time; understanding this can shift us from a limited belief to a growth mindset.

Capacity is energy, and some people’s jars are more consumed than others. Parents have less available capacity than non-parents, and the sick have less than the healthy.

Capacity is mental faculties. Some jars are cluttered with anxious thoughts, trauma, or grief, leaving people with fewer faculties for other things.

Capacity is motivation. Those passionate about their work have more incentive to invest than those whose interests lie elsewhere.

We might feel we have a smaller jar than others, as we may not respond well to stress and have spiraling thoughts consuming mental bandwidth. But this belief conflates two concepts: The size of the jar and the space available within the jar.

Our total maximum capacity might not grow. Anxiety consumes mental space, like calcified soap scum coating the wall of a jar. This jar junk lives rent-free, stealing real estate from a more responsible, paying tenant. Confronting anxieties won’t increase the size of our jar, but it can improve our usable capacity.

Busy parents can’t increase the hours in a day, but they could increase the usable hours by outsourcing activities like cooking or cleaning. Company leaders cannot generate more energy but can delegate administrative tasks to increase their capacity for strategic decisions.