20 November 2022

Going Reptilian

The world is complex. But navigating complexity is taxing, so we gravitate toward simple dichotomies of this or that, one or two, red or blue.

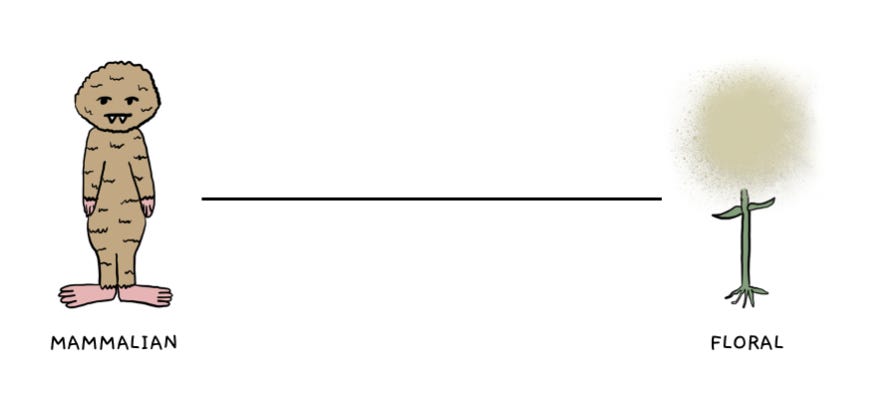

Way of the Mammal

Consider the classic debate of quality vs. quantity. Should we expend our resources on many things (i.e., Buy hundreds of different stocks to hedge our bets) or funnel into one big thing (i.e., Invest in a single business venture)? The latter method is mammalian.

It’s our nature to invest a lot in a little. Like a bear caring for a cub or human parents nurturing their two to three children, it’s common for mammals to choose quality over quantity.

Going mammalian can lead to innovations and profound accomplishments, but it can come at the cost of misplaced investment. The way of the mammal requires something often in short supply: Conviction. How can we know we’re pursuing the best outcome without faith in the chosen track?

Way of the Dandelion

In Information Doesn’t Want to Be Free (2014), Cory Doctorow argued that creating things on the Internet required a paradigm shift. Instead of devoting ourselves to a magnum opus, we could adopt the way of the dandelion and spew tiny “seeds” on blogs, podcasts, and videos. In a complex and uncertain world, spanning wide and seeing what sticks increases our surface area for success. Doctorow’s radical shift from quality to quantity humbly acknowledged our limits. We don’t know what will succeed in a vast new world, so a “floral” strategy could serve us.

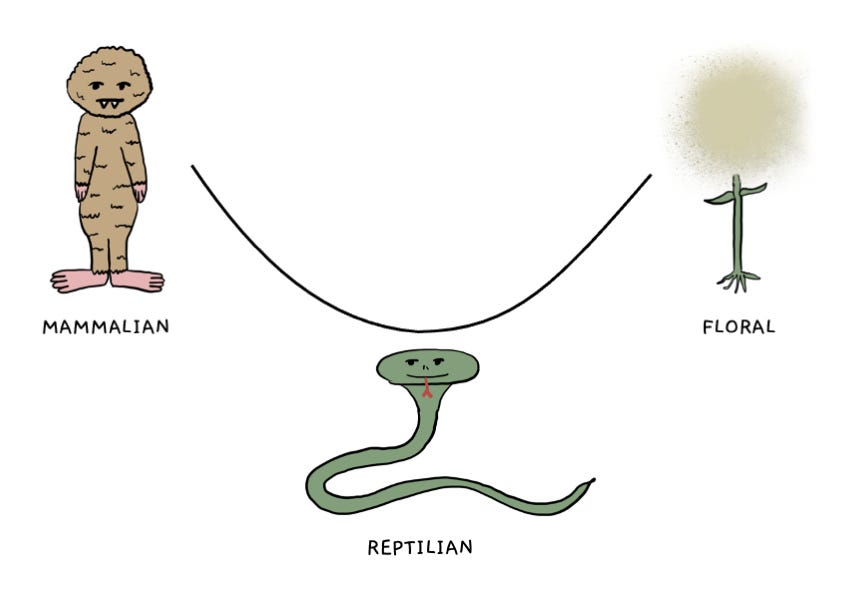

Way of the Reptile

Most reptiles lay eggs to reproduce. Unlike a plant that spews thousands of seeds or a mammal that live-births a few offspring, reptiles lay 3 to 20 eggs (on average, for most snakes).

Reptiles subscribe to neither quality nor quantity yet accomplish a bit of both. They lightly invest in a dozen eggs—place them in a nest, keep them warm, and protect them—to give their offspring a fighting chance upon birth. This investment isn’t as intensive as mammalian parenting but is more than a dandelion’s random spewing.

Venture capital firms act like reptiles. They might seed twenty companies with the expectation that 18-19 will fail. But the one to survive could be a huge success and offset the cost of all experimental investments.

While this cold-blooded reptilian approach might feel unnatural, we could consider it for our work by picking a handful of small bets. We could invest time and energy to create a prototype, then release it “into the wild” to see how it performs. If successful, it could grow into a larger beast; if not, we wouldn’t lose much.

Going Reptilian

To go reptilian, we must apply discretion to our list of ideas. We may have a hundred potential projects, but—if we’re honest—we know most of them are crap. Using judgment, we can narrow that list to ten that “have legs.”

We could write a single page about each idea—what it is, who it’s for, how we could do it, and why it matters. By developing this idea with focused thought, we produce an egg.

Once we have an egg, a rounded-out idea, we incubate it into a prototype. For instance, we could write a scene for a story or build a lightweight app. When the egg hatches, we can push it from the nest and get real-world feedback on its performance. Does anyone use it? How do people like it?

As the turtle represents, my newsletter is an exercise in the reptilian method. Rather than a slew of daily tweets or spending months on a book like I did in years past, a weekly email lets me experiment quickly and see how a concept lands.

We can go reptilian.