10 November 2022

Thinking Caps

Are we anything but the roles we play?

Be it at home, work, or play, we wear a dozen hats: Parent, friend, volunteer, manager, peer, runner, stamp collector.

Our Own Hats

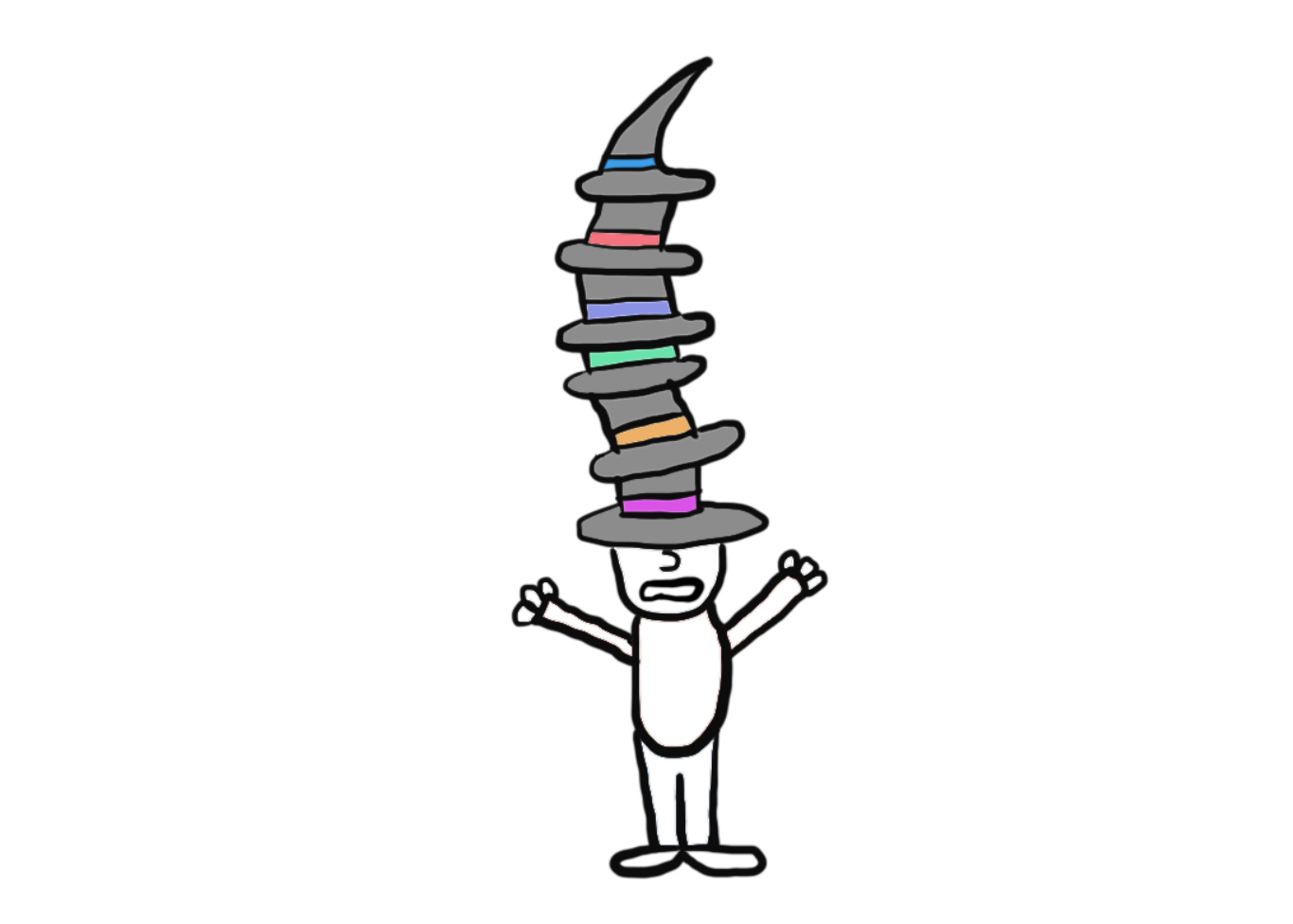

When I write this newsletter, I picture myself wearing four hats. The first is obvious: The Writer Top Hat. Under the brim, I’m thinking about ideas and how to articulate them. My mind wanders far and wide, and I don’t fret about reeling it in.

Because clarity is the job of the second hat: The Editor Fez. When wearing the Fez, I’m focused on making jumbled ideas more digestible to readers. What could I axe or reshape to craft a compelling message?

The third hat is the Illustrator Beanie. When inside the knitted cap, I consider the visuals to portray ideas I’ve written.

When not gathering dust, I wear the Marketer Ball Cap and think through sharing mechanisms. On which platforms could I publish the article? How do I tag it for SEO?

The Hats of Others

Teams with diverse perspectives generate better outcomes, and assigning hats can accomplish this.

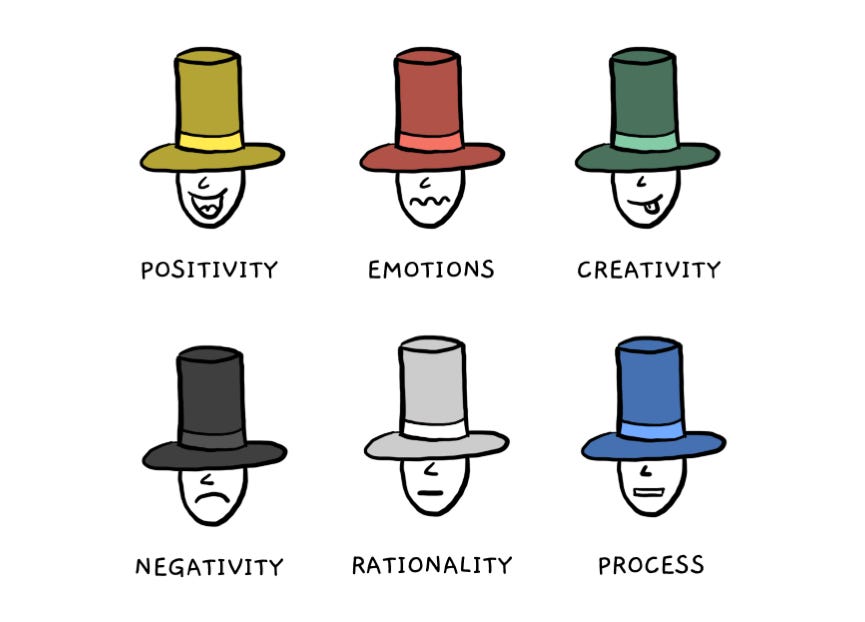

Edward de Bono proposes “Six Thinking Hats” in his book of the same title to guide group decision-making:

- Yellow for positivity, to highlight the benefits of opportunities

- Black for negativity, to consider the downsides with critical thinking

- Red for emotions, to use gut feelings and assess how people will react

- White for rationality, to use reason to analyze available data

- Green for creativity, to generate ideas freely, without censorship

- Blue for process, to recall the big picture and steer the group toward progress

- Cycle through each hat as a group. For instance: Begin with a review of the data (White Hat), discuss opportunities (Yellow Hat), and then consider risks (Black Hat), or

- Assign a hat to each member. For instance: Padma wears the White Hat, Jose wears the Red Hat, etc.

We should be deliberate about the points of view we want at the table. While we might expect Rational Padma to bring a data-driven mindset, explicitly asking for that perspective will make our intentions known and encourage participation.

These six hats aren’t the only approach to group decision-making. IDEO, a renowned design agency, advocates specific roles to manifest ideas in The Ten Faces of Innovation. Some people may gravitate toward top hats, others ball caps.

Conversely, the Catholic Church pioneered the “devil’s advocate” approach when considering a person for sainthood. A devil’s advocate was assigned to argue against the nominee to uncover any character flaws. Although the devil’s advocate might disagree with his claims, he dons the devil’s horns for the team’s betterment—combatting groupthink with critical thinking.

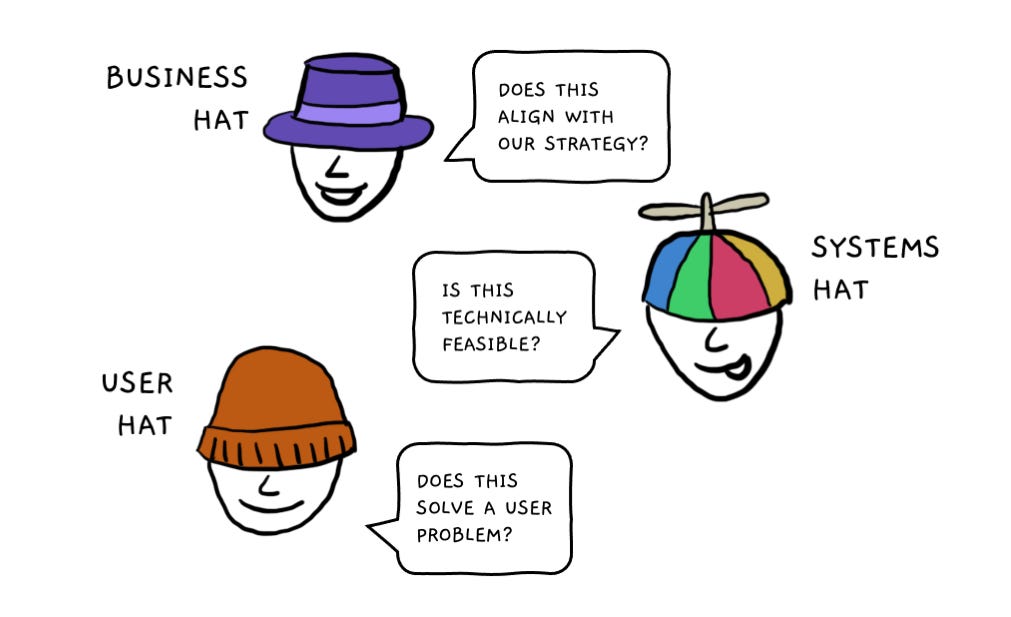

We needn’t follow any framework religiously (ha), for we can assign hats per the circumstance. Imagine a three-person product team launching a new feature. The product manager might wear the “business hat,” the designer the “user hat,” and the engineer the “systems hat.” While the engineer might deeply understand the business needs, she takes responsibility for system considerations.

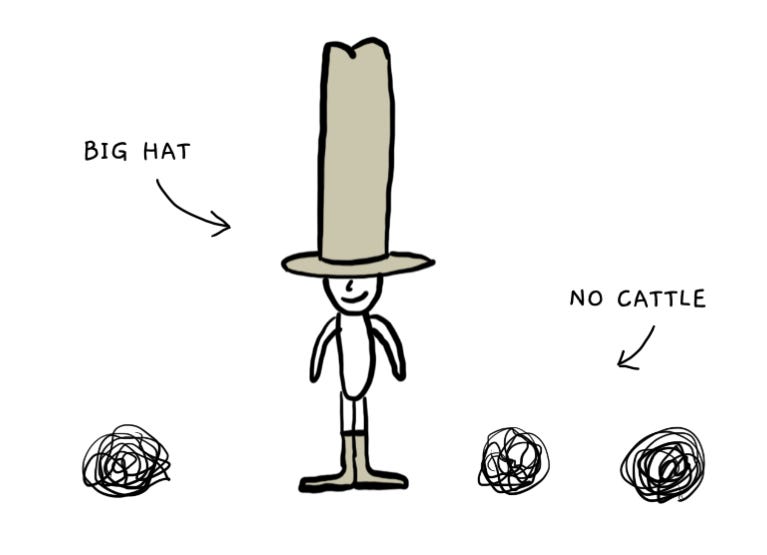

There’s an old cowboy idiom: “Big hat, no cattle.” A cowboy with a tall, fancy hat might talk a big game, but none of that matters if he doesn’t hold cattle—sufficient experience, resources, or training that qualify him for the perspective.

For a thinking cap to work, the wearer must be worthy of the crown.